Async/Await — What Happens Under The Hood

Using Async/Await is simple, but there is a lot hidden in these two keywords. To fully understand how it works we will have to run through a bunch of concepts, some of them a little fuzzy but I expect to be able to unveil the mysteries behind Tasks, Threads and Concurrency. Grab your cup of coffee and come with me.

Concurrency is not Parallelism

These two subjects ofter are mixed up, but they are far to be the same, and understanding the differences is essential to our subject here. Let’s dig into the differences between these concepts.

Imagine that you have a really complex equation that can be split into two smaller parts and you need to write a program to solve this equation. Since the equations can be split up does not make sense to wait for part 1 to be completed for you to trigger the calculation for part 2. In the ideal world, the correct would be to calculate them at the same time. But this is only possible if you have a processor with more than 1 core and here is why.

Operating systems have what we call Task Scheduler. The duty of the Task Scheduler is to provide CPU time for each process.

A process is an instance of a program being executed, and each process is subdivided into threads. Threads are sets of instructions/code that will be executed by the scheduler at a given time.

Back then the processors used to have just a single core and still everything seemed to be running at the same time, how this could be possible? The thing is that the Task Scheduler is really efficient at distributing time and the time slices are very, VERY short, so it seemed that everything was running parallelly, but they weren’t, it was just one after the other at a really fast pace.

Ok, I said that each slice of time is really short. What happens if my set of instructions did not finish in this amount of time?

The thread is suspended and the CPU time is given to the next one.

When this occurs it is possible that some variables that are being allocated inside the CPU cache need to be released to provide space for the variables of this new thread and this causes an overhead.

The more processes you have more times this operation will happen. That’s one of the reasons the computer gets slow when you have a lot of programs running and just a single core to handle everything.

The algorithm generally used to manage all these things is called Round-Robin and the process of putting another thread to execute is called Context-Switching.

Back to our calculation, if we had a single-core processor even if we split the calculation into two threads, as we saw, they still would be executed sequentially. For real parallelism, you need to have more than one core, so that each core can execute the code independently and at the same time (for real).

I explained all this stuff about parallelism to make it clear: Concurrency is different from parallelism, they can be used together but are far from being the same thing. Parallelism is doing more than one thing at the same time, concurrency is doing something else while someone else performs a thing you are waiting for.

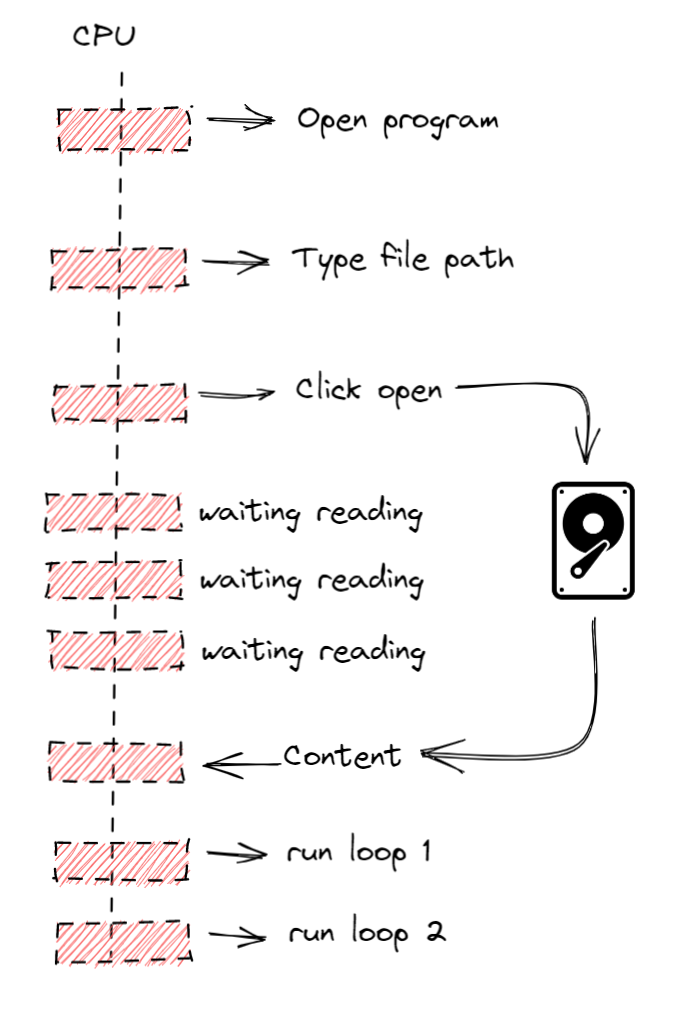

Let’s imagine that we have a single-core computer running a C# program we built, this program consists of a text file reader with a simple UI.

We start the program. When this happens until we type something the program is idle since we have nothing being executed, now we type the value. The action of typing requires code activity to show what we typed into an input field, so there is code being executed at that thread. Now We click to open the file, the OS will look for that file and provide us the content in bytes that we need to parse and show on the screen.

Supposing we are using a synchronous OS call we would be ending up with something like the diagram below.

The CPU will not wait for your processing to finish, it will continue the round-robin process, but our thread will not process anything else until we get the return of the content.

Notice that while the OS is reading the data from the disk our thread is still running, but in fact, no code is being executed since we are just waiting for the OS to return the content. The thread is locked and we are doing nothing with this CPU time, not good right? Actually, it is a little worst. Our program will get totally unresponsive to any kind of input (keyboard or mouse) since our thread is waiting for the response and cannot do anything else. Is like you watching and waiting for the water to boil and doing nothing until it happens.

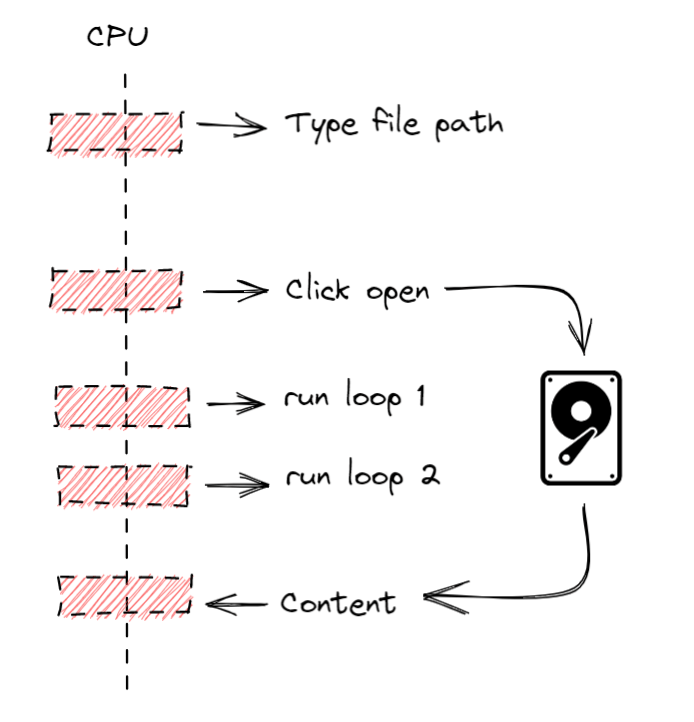

If we use asynchronous computing we would be ending up with the diagram below

Now our thread is free to process other things while we don’t get the response from the Operating System

This is what happens: We ask for the content of the file and while the OS is looking for it we set free the thread responsible for the call to do other things. When the OS got all the data, a callback is evoked and the code execution will continue and the text will be displayed. This approach will make the UI responsive since the thread can process keyboard inputs or mouse movements while it is waiting for OS response.

We call asynchronous because while we await for something to happen we can do another thing. Whenever we are performing a non-cpu-bounded process, it is a good idea to use asynchronous programming.

Before we get deeper into how asynchronous works let’s talk a little bit more about threads, more specifically about the ThreadPool.

ThreadPool

Generally in a .NET process, the amount of threads is directly related to the number of processor cores you have available, a simple 1 to 1. But if .NET thinks more threads are necessary for the system to perform well it will create more threads by itself and these threads will be part of the ThreadPool.

ThreadPool is a long-lived collection of threads available to execute tasks. The reason for these threads to be put in a long-lived collection is to make it possible to reuse these threads.

When a task attributed to a thread is done, this thread is put again at the ThreadPool to be reused in a future execution

Creating a thread is a computing expensive task and they take some megabytes of memory also, so a big amount of threads is as bad as a small amount of them, do you remember the Context-Switching process? A lot of threads equals a lot of context-switching. That’s why is always good to rely on the ThreadPool engine that knows how to tune those things instead of creating a lot of threads explicitly and hoping for the best.

Think about a WebAPI, if our webserver has only two cores we will have two threads, but what will happen if we have 2 requests running and a third one is triggered? .NET will notice that our 2 threads are busy and will create another one to handle the request. If we use asynchronous programming the chance of these 2 threads being fully blocked is way lower since the most timing-consuming process use to be I/O related and the I/O operation is no longer blocking the existing threads.

You could argue that nowadays most computers have a lot of cores and they can handle well heavy loads by splitting the processing among those cores. Actually, they are very powerful, but lately, we started to use more and more a technology that relies almost on single core environments: Containers. Containers tend to be single-core and in this scenario having a well-sized ThreadPool is essential, making asynchronous programming crucial for your application to perform well.

Now that we took a look at Threads and ThreadPool, it is time to understand Tasks

Tasks

Basically, we can consider a Task a piece of work to be executed.

Imagine that we have a department where you and a friend are responsible to go to the archive and request a specific document for the person that manages the archive sector. You have a supervisor who talks to those clients, fills a requirement and delivers it to you.

Client 1 arrived. Your supervisor talks to the client, get their request, fill the formal requirement and as he sees both you and your friend at the corner, he randomly chooses one of you to go to the archive to get what he needs.

In this scenario, we have the following.

- The client is a piece of code that asks for some data (I/O)

- The supervisor is the ThreadPools that manages the threads and dispatches the work (Tasks) to be done.

- The threads are you and your friend. You are the hard workers, the ones that will perform the given Task.

- The Task is a piece of work that will be performed by the thread (you). In this case, go to archiving sector and ask the responsible for a document.

The nice thing is that the ThreadPool can receive a bunch of Tasks and the tasks will be dispatched as threads get available. If the ThreadPool gets a lot of tasks pending, a new worker can be create to join your team and increase the performance, but only if it is worth it, hiring (create a new thread) is expensive :)

When you get back from the archiving sector you don’t just return with the document, you return with your task requirement. In this requirement, you have some data like the ID of that Task and its Status. Attached to this requirement you have the result of this task, in that case, a document(or no document if it was not found). That’s why Task has a Generic parameter, it always returns a Task of something (if you expect a return value from the method). For your research at the archiving department, it is a Task<Document>.

Now you got the document to return to your client. All you have to do is call him in the waiting room, since your client requested an async task, it will not stay at the counter waiting for you to get his document. Soon we will discover how to call your client to deliver their request, next in line, please.

Now that we got Tasks also, it is time to understand the workflow of an asynchronous code.

Going asynchronous

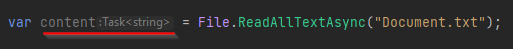

Let’s get the content of the Task you performed

Response of an async method is always a Task

As we can see the method does not return a string, it returns a Task with a string that may contain content.

If you use the VisualStudio Intellisense or other type of auto-completion or hinting feature you will see two methods that will return the result string: .Wait() and .Result(). DO NOT use those methods, these are blocking methods and your code will not run asynchronously.

If you execute your job in an asynchronous way, while the archiving responsible person looks for a document you can go back and grab a new task to deliver to another person in the archiving department. Using .Wait() or .Result() will imply into you waiting for the person to look at the whole archiving until he finds(or not) the document and give it back to you.

Let’s see a way to run this asynchronously.

public Task<string> GetDocumentContent() { var content = File.ReadAllTextAsync(@"Document.txt") .ContinueWith(t => { return t.Result; }); return content; }

The ContinueWith() method receives an Action<Task<string>> that will be triggered just when the Task is completed, in that case, when you get back with the formal requirement and the document.

But what happens if the document is not found? In that case, your client will receive an empty response, since this code does not deal with Exceptions. To handle them you have to manually implement this.

public Task<string> GetDocumentContent() { var content = File.ReadAllTextAsync(@"Document.txt") .ContinueWith(t => { if (t.IsFaulted) { Console.WriteLine(t.Exception); } return t.Result; }); return content; }

Ok! now we have this working, but the code is awful. 14 lines to read a file? No way.

That’s why the C# team implemented at C# 5 the async/await keywords. At the example below we no longer just print the result, we actually get it back and return it. To make something like this using the old fashion async is really hard since we get a lot of synchronism problems. Using the new way of doing things, our code gets like this.

public async Task<string> GetDocumentContent() { return await File.ReadAllTextAsync("Document.txt"); }

Way better, right? Note that the method signature changed from public Task<string> to public async Task<string> and now we have the await keyword after the return statement. Why does this happen? Because now a lot is happening under the hood and that’s what we will see right now.

Async/await — Opening the hood

Here I’ll use a decompiler called ILSpy. This tool can read the IL code and make it a little more readable to us.

Here is the synchronous version of this code

This

public class MyClass { public string GetDocumentContent() { return File.ReadAllText("Document.txt"); } }

Becomes this

public class MyClass { public string GetDocumentContent() { return File.ReadAllText("Document.txt"); } }

Same thing. No difference.

Now let’s take a look at the asynchronous version.

This

public class MyClass { public async Task<string> GetDocumentContent() { return await File.ReadAllTextAsync("Document.txt"); } }

Becomes this

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Auto)] [CompilerGenerated] private struct <GetDocumentContent>d__0 : IAsyncStateMachine { public int <>1__state; public AsyncTaskMethodBuilder<string> <>t__builder; private TaskAwaiter<string> <>u__1; private void MoveNext() { int num = <>1__state; string result; try { TaskAwaiter<string> awaiter; if (num != 0) { awaiter = File.ReadAllTextAsync("Document.txt").GetAwaiter(); if (!awaiter.IsCompleted) { num = (<>1__state = 0); <>u__1 = awaiter; <>t__builder.AwaitUnsafeOnCompleted(ref awaiter, ref this); return; } } else { awaiter = <>u__1; <>u__1 = default(TaskAwaiter<string>); num = (<>1__state = -1); } result = awaiter.GetResult(); } catch (Exception exception) { <>1__state = -2; <>t__builder.SetException(exception); return; } <>1__state = -2; <>t__builder.SetResult(result); } void IAsyncStateMachine.MoveNext() { //ILSpy generated this explicit interface implementation from .override directive in MoveNext this.MoveNext(); } [DebuggerHidden] private void SetStateMachine(IAsyncStateMachine stateMachine) { <>t__builder.SetStateMachine(stateMachine); } void IAsyncStateMachine.SetStateMachine(IAsyncStateMachine stateMachine) { //ILSpy generated this explicit interface implementation from .override directive in SetStateMachine this.SetStateMachine(stateMachine); } } [AsyncStateMachine(typeof(<GetDocumentContent>d__0))] public Task<string> GetDocumentContent() { <GetDocumentContent>d__0 stateMachine = default(<GetDocumentContent>d__0); stateMachine.<>t__builder = AsyncTaskMethodBuilder<string>.Create(); stateMachine.<>1__state = -1; stateMachine.<>t__builder.Start(ref stateMachine); return stateMachine.<>t__builder.Task; }

WOW! Our method became a struct? Yes, it became a Struct and it is full of stuff.

Let’s dig into this and understand what’s going on

First of all, notice that your struct implements the IAsyncStateMachine interface that exposes two methods MoveNext() and SetStateMachine. We will talk about those methods soon, but first, we need to describe what a State Machine is.

A State Machine is a mathematical model to represent logical circuits and their state which is muted by events and can go from one state to another in a certain sequence.

The state machine here is used to set the state of our Task.

- Line 9 We declare a

TaskAwaiter<T>property that will hold an object that represents an await for a Task conclusion. Note that this is declared at the struct root level. - Line 69 : We create a new State Machine.

- Line 70: Represents a builder for asynchronous methods that returns a Task. Also provides a parameter for the result. Note that the generic parameter is the same as your Task result type.

- Line 71: We set its state property to

-1 (Created). This number will control whether the Task is finished or not - Line 72: This

Start()method will call ourMoveNext()method that will actually run our code. - Line 13: Set the

numvariable as our State Machine status, in this case-1 (Created) - Line 17: We declare a

TaskAwaiter<T>property that will hold an object that represents an await for a Task conclusion. It is the same thing as line 9, but now it is a method-level variable - Line 18: We check if

numis different from0 (Awaiting). At the start, it always will be different, since we declared it as-1 (Created)in line 71. This block inside the if statement will trigger our asynchronous code. - Line 20: We trigger our read file statement and attribute it to the

awaitervariable. - Line 21: Instantly we check if the task is already completed. If the job to be done is performed really fast then it will automatically go to line 35 and set our result variable as the result of that task

- Line 44: We set the state machine result content with the result of the operation.

- Line 73: Gets the content of the builder and returns the Task that was executed. If things are executed fast we have our execution finished here.

- Line 23: If the Task is not completed then we will set the state as

0 (Awaiting), soon you’ll understand why. - Line 24: We attribute the

awaiterlocal variable to the<u>__1variable. This is important because of the next step. - Line 25: The

AwaitUnsafeOnCompletedmethod is called. Here we have a little to talk about.

Note that the method receives two parameters the awaiter and the struct itself. Note that they are passed by reference, why? Because both are structs and structs are value-types. That means that when we pass these properties to another method their whole value has to be copied and since these are big objects this could impact performance, so they are passed by reference to avoid any trouble regarding this matter. AwaitUnsafeOnCompleted will also need to access the same instance to make the thing move on.

AwaitUnsafeOnCompletedmethod will be responsible to call our MoveNext() method once the async operation has been completed. That’s why we pass this as the second parameter and, it will also change the state of awaiter state to Completed.

Now the operation has been completed and the MoveNext() has been called again. Now the if at line 18 will not be satisfied since we set this value as 0 (Awaiting) at line 23 at the previous call. The code will go straight to line 29.

- Line 31: We set the

awaiterinternal variable as the result of the operation - Line 32: We kinda reset the

<>u__1variable, it will end up having a value inside, but the Task property will be null. - Line 33: We reset the state of the State Machine to its initial value.

- Line 37: If an exception happens that’s when we will handle it. We set the state as

-2 (Completed)and set the exception, then we return without setting the result. - Line 43: We set the state as

-2 (Completed). - Line 44: We set the state machine builder content with the result of the operation.

- Line 73: Gets the content of the builder and returns the Task that was executed

Wrapping things up

Tasks, Threads, and ThreadPools are subjects that are really worth understanding how they work to be able to improve your code, specially Threads where a simple mistake can lead to a code with huge performance issues and hard to maintain.

Async/await on the other hand does not require a lot of expertise nor deep knowledge about its internal mechanisms to be used, but there is a lot hidden down beneath. We took a brief look into how it works but there is still a lot going on, if you want to I can write a second part going a little further into async gears

If you have questions about the subject leave a comment and I’ll do my best to answer you.

See you in the next article :)